ARTISTS ON ARTISTS

Artists have a different perspective on art and other artists than what critics may have. The terms of the relation shift between rivalry and envy, and reverence and praise.

Martin Gustavsson on the Violent Freedom of Miriam Cahn

Martin Gustavsson on Miriam Cahn

Miriam Cahn o.t., m. 2. 1983 chalk on paper 12 elements: 180 x 450 cm (overall). Photo: Olivier Roura courtesy Galerie Jocelyn Wolff

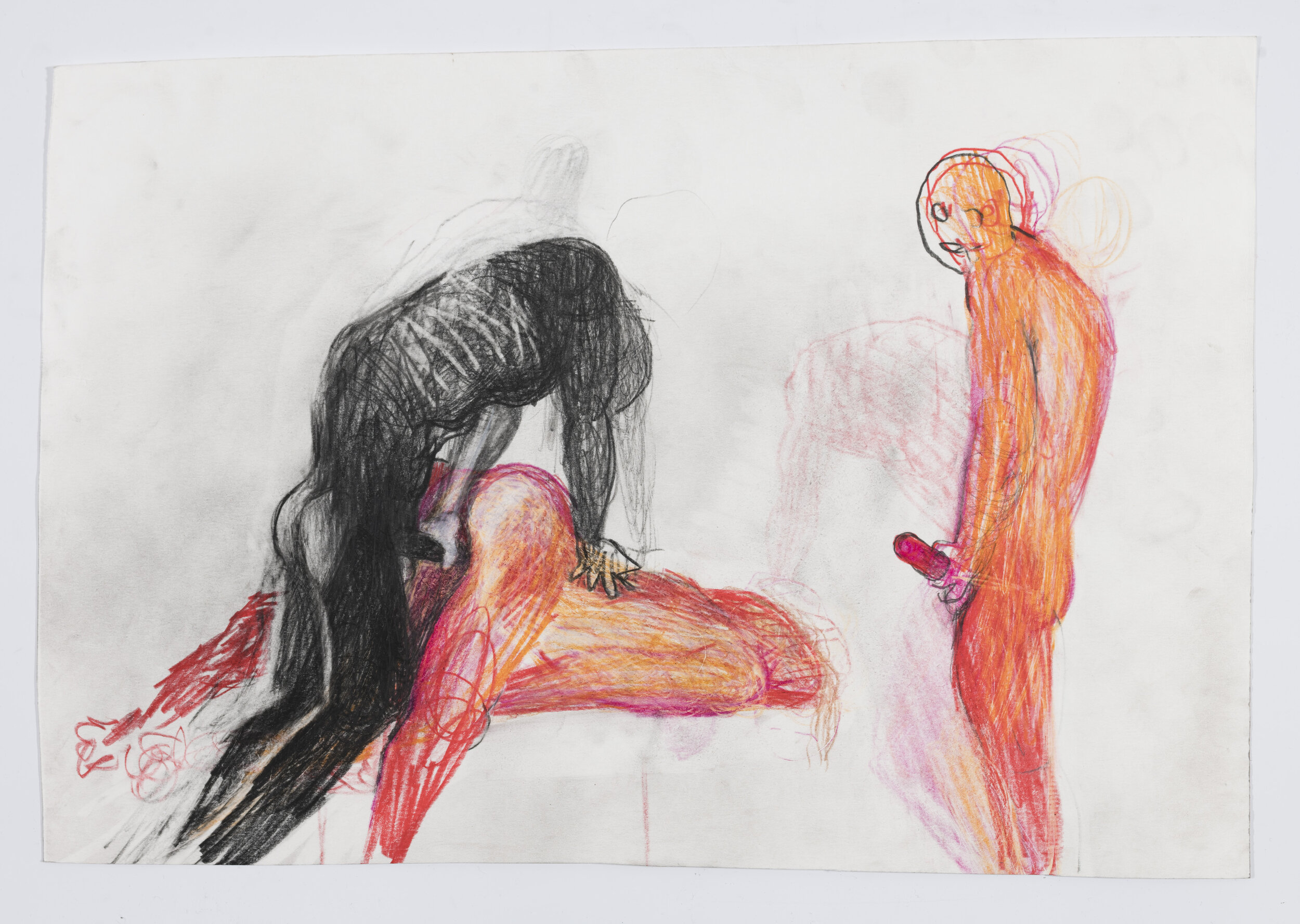

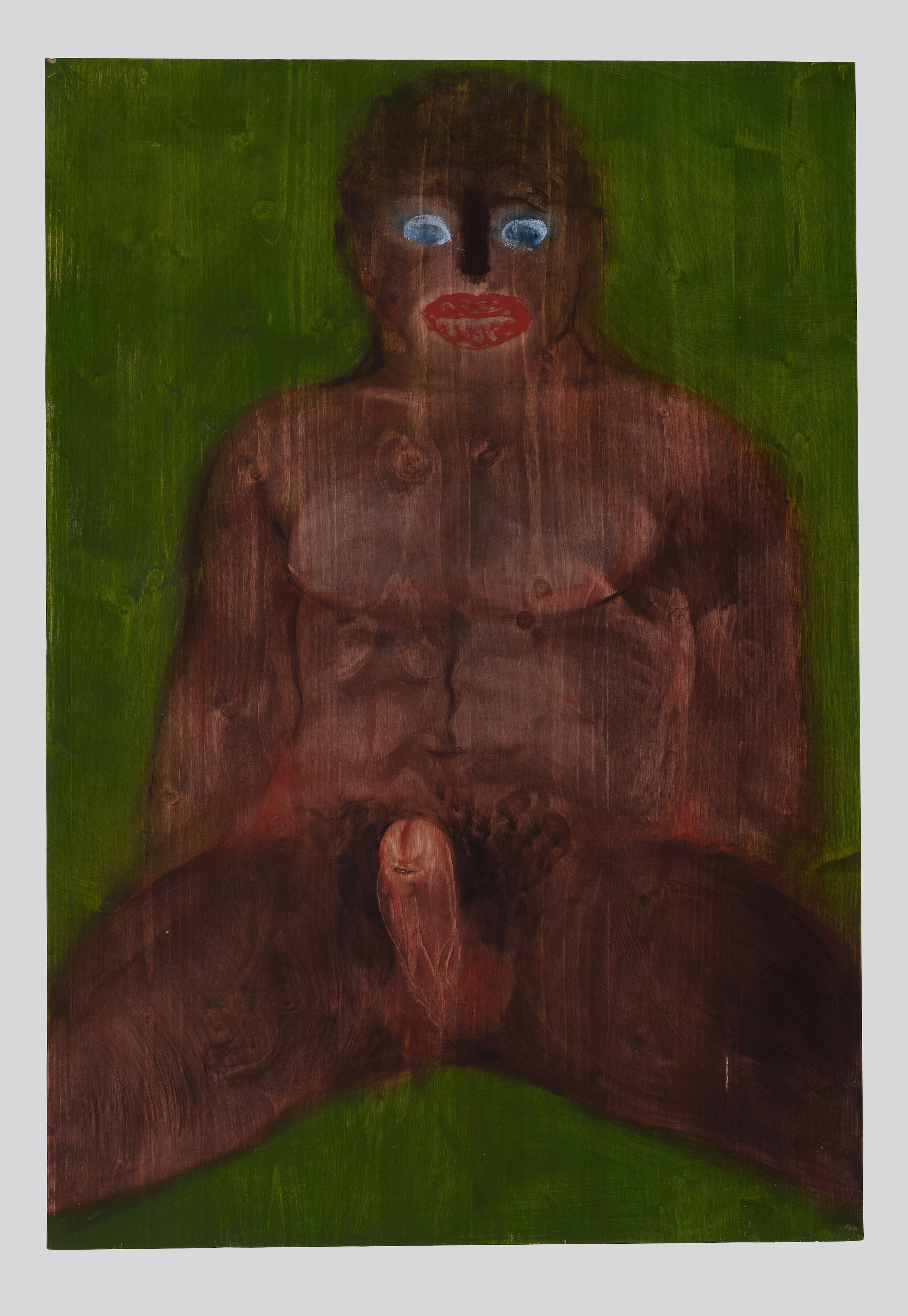

People, dogs and houses in a sea of burning colors. These paintings, Miriam Cahn’s paintings, are peopled or inhabited by creatures humanoid or other worldly as though different dimensions have crashed into one another, fertilized and cross coupled. I think I have never encountered color that so strongly puts me in emotional states that register on an unknown scale. Her characters often have sex, quite violently, or give birth to children; sometimes they are fighting, on other occasions they are isolated. Erect limbs and swollen body parts on creatures that do not seem to be able to live with them, but confusedly try to find a place that doesn’t confuse. Other figures look out from the paintings, fixing our gaze with a force that nails us to the ground, solidified. It’s a heightened sense of being, not always pleasurable but always gratifying.

Not so long ago, I would often go to Berlin to look at art. For me, those trips were a bit like going on a Spa trip. A place to clear one’s head, meet friends and charge the batteries by engaging properly with looking at Art. One such time I visited a gallery without knowing that it would change not only how I look at painting but also how I myself live with painting. It was my first encounter with Cahn’s artworks and it took a while to allow myself to access them. They seemed too colorful, too hippie like, just in so many ways too much. I became aware that they couldn’t be thought. I would have to start feeling them to understand my reaction. I know now that I had been looking for them. In my own work I had made several attempts in this direction, Wrath of God in 2007 is perhaps the one that feels most relatable in terms of content. I do feel though that I had to somehow mitigate or reformulate my work in order to be understood, or perhaps counted. In meeting Cahn’s work however, I could better understand my own difference, vital to all art and crucial in making the personal political. Still true to this day.

Miriam Cahn, Soldat 16.12.2010 / White Supremacy Porn 15.12.19 / Im Dunkeln 28.12.19 (Photo: François Doury)

For several years I have taught at various art academies where I have met young artists who now say they want to feel. I see this as a desire to reclaim subjectivity. Perhaps a cyber subjectivity mixing up the old canons in unseen ways. A wish to attain real difference and feel the visual and political power inherent in a position seeming emotionally true, if there is indeed such a thing. This is what I feel Cahn is doing. There is a clear difference from days gone by when as a painter you would be expected to evince watertight theoretically substantiated reasons for wanting to touch a brush.

Of course, this desire for emotionally conditioned works paves the way for other forms of experiencing and producing art over time. Cahn is today in her seventies and to my knowledge has always worked with an emotional force that only now may be felt. During the seventies, she worked with performance and charcoal drawings, perhaps without getting a major place in the art world at that time. Of course, this was also due to the fact that she is a woman, not so much of an advantage in a male-dominated world. Her life and practice are political and feminist, using her exhibitions to comment on ongoing events in the world such as the refugee crisis and the struggle for equality. What is embodied is vulnerability, the memory of war manifests itself.

Miriam Cahn, installation shot of the exhibition notre sud, Galerie Jocely Wolff, Paris 2020. Photo: Chloé Philipp courtesy Galerie Jocelyn Wolff

Cahn has thus remained where her interests are and has waited for us to follow her. Her own family fled the persecution of Jews in Germany during World War II, which of course has also informed her sensitivity.

What was it then that struck me when I first encountered Cahn's work? I experienced a violent freedom, or what I perceive as freedom. An artist and a work, which without looking over its shoulder seemingly goes its own way, so completely clarified what it means to make decisions based on the experience of embodying difference. I became aware of myself, that is, I became aware of which of my painting decisions were my own and which others were given to me by a certain type of education, class affiliation, gender and other categories. Similarly, I was also made aware of which decisions had been made in opposition to those invisible rules. Miriam Cahn showed that it was possible to throw a lot of excess luggage in the bin. There is another figurative painter who I feel tries to embody the difficulties surrounding representation and abstracted emotional schizophrenia (though in very different ways): Jenny Saville. In a filmed conversation with Simon Groom, Director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, she says that she previously painted transsexual people whereas now her painting practice is Trans. The paintings thus no longer only describe. They are.

Paul Preciado writes in the catalogue for the ‘ I as Human’ exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw:

“You say: Do you not realize that this is not your portrait? Do you confuse your face with any mass of transuranic flesh?The intensity of your blue will set the computer of the world on fire and the skin of nuclear power plants will fall revealing a woman’s belly.

Utopia or death. Color or death. Painting or death.”

So can painting change our lives? Clearly yes!

If we let it.

A visit to Miriam Cahn’s studio in 2020 by Sebastian Messerer can be found here.

All images of Miriam Cahn’s work: courtesy Galerie Jocelyn Wolff

Martin Gustavsson, The Deluge, 2007, diptych 2x250x190cm, oil on linen. From the series Wrath of God